EXHIBITION DETAILS

Portfolio Showcase Volume 13

May 13 - August 22, 2020

Each submitted portfolio is evaluated as a cohesive body of work by the Juror. One artist will be selected to receive the $1,000 ShowCase Award and be offered a solo exhibition at C4FAP. Ten photographers will be chosen to have their 12 image portfolio published in the Portfolio ShowCase 13 in-gallery and online exhibition complete with artist website links.

JUROR | Barbara Tannenbaum, Curator of Photography, Cleveland Museum of Art

Selected artists:

Carl Bower, Suzette Bross, Troy Colby, Sharon Draghi, Anna Grevenitis, Glenna Jennings, Dave Jordano, Andy Mattern David Obermeyer, Walter Plotnick

ShowCase Award | Carl Bower

STATEMENT

Thinking over this year’s Portfolio Showcase submissions, I was surprised by how many are keenly relevant to life during the COVID-19 pandemic. The photographs were made and submitted long before any of us heard of the novel coronavirus and were juried as it was just beginning to be discussed. A wide variety of types of photography were submitted to the competition—landscapes, formal exploration, abstraction, documentary, staged works, still life—but relationships and emotions were dominant topics and yielded some of the strongest portfolios. Perhaps the national mood was already turning inward, perhaps it was merely chance. Either way, the chosen portfolios have much to offer us as we ponder our current situation.

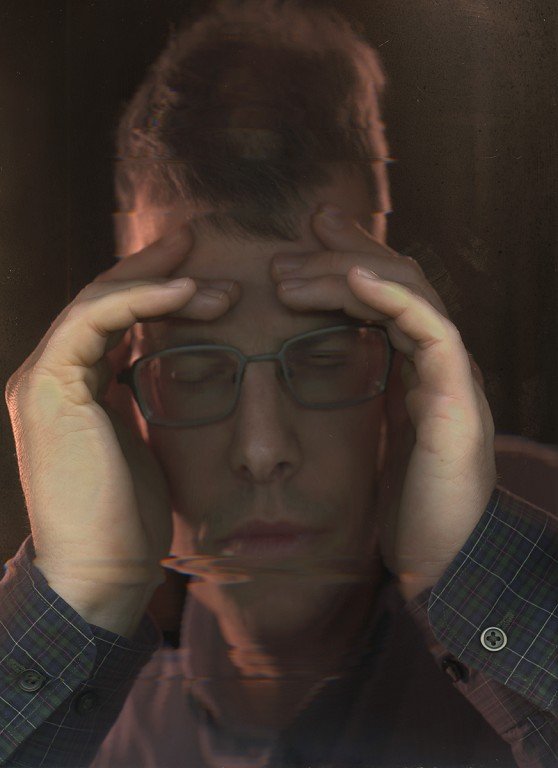

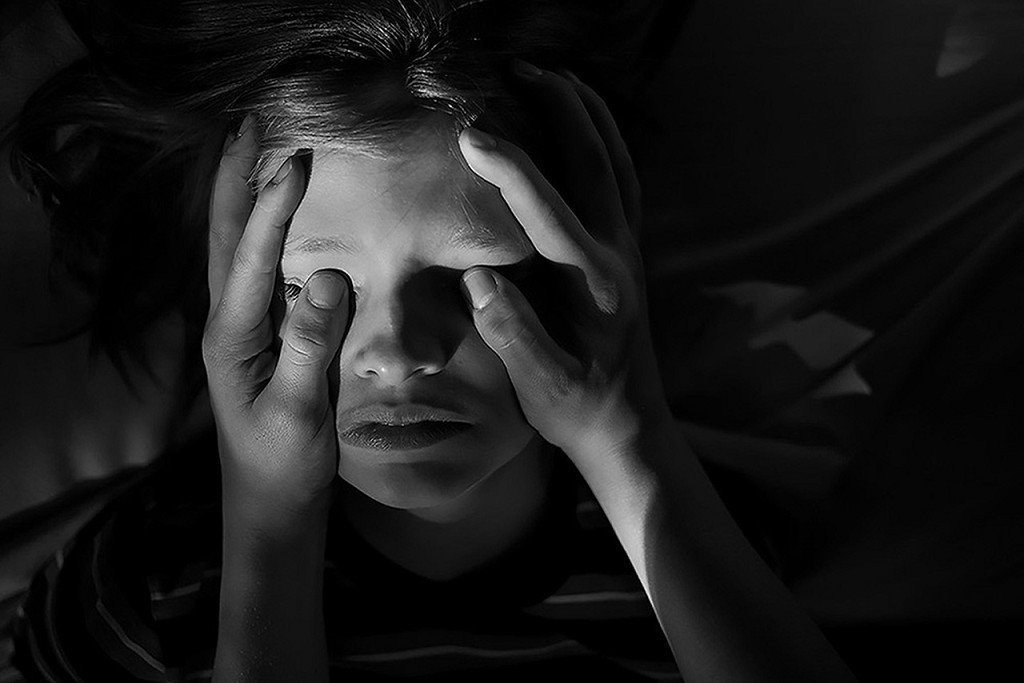

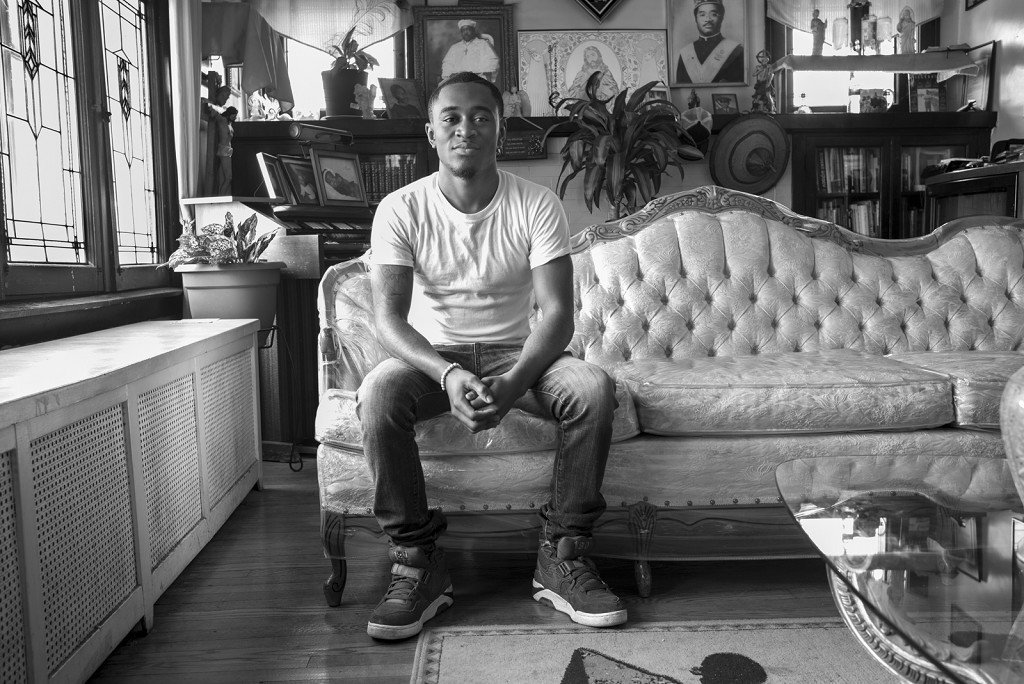

Intimacy and distance are topics addressed by Carl Bower, David Obermeyer, and Suzette Bross. Bower’s powerful yet reserved portraits in Private Fears document individuals reflecting on the anxieties that shackle them and shake them to their very cores. Before asking his subjects to bare their emotions to him and his camera, he shares his own fears with them. The intimacy that Bower established is rewarded with deeply insightful portraits. David Obermeyer’s shots of at-risk young people are more documentary in aim, and his sitters far more guarded. These youths, enrolled in a church program that helps them reconnect with society through full-time employment, are wary about revealing any vulnerabilities. In Suzette Bross’s series For the Glass, fingertips and faces press against the glass of a scanner. Her sitters seem to try to establish physical contact through the picture plane, an impossible task and a poignant one in this time of physical distancing. Bross prints these images larger than life size, enhancing the tension between intimacy and a sense of remove.

The closeness—which sometimes become claustrophobia—of family and home is explored by three of the selected artists. Sharon Draghi’s staged and candid color shots of her family are set in her home and on her street, echoing the collapsed universes and state of interiority most of us have been experiencing during quarantine. Colby’s black-and-white series The Fragility of Fatherhood subtly suggests the depth of love, hope, but also uncertainty and restlessness within the tight bond between the artist and his son. A similar attachment is the subject of black-and-white portraits by Anna Grevenitis of the artist and her daughter, who has Down syndrome. Contrasted with their closeness is the presumed curious gaze of the outsider/viewer. It is unabashedly returned by Grevenitis, who stares directly into the camera.

As sheltering in place orders caused us to withdraw into our homes, cities became skeletons stripped of the chaotic, life-giving flow of people and traffic. This emptiness is presaged in Dave Jordano’s haunting scenes of a deserted Cleveland at night. Here and there a lone figure guards an open convenience store, and the palette is warm, but the barren streets nonetheless invoke an otherworldly chill. A stunning contrast—and a reminder of the “old normal”—is found in At Table by Glenna Jennings. These vibrant scenes evoke not just the gustatory but also the social pleasures of dining.

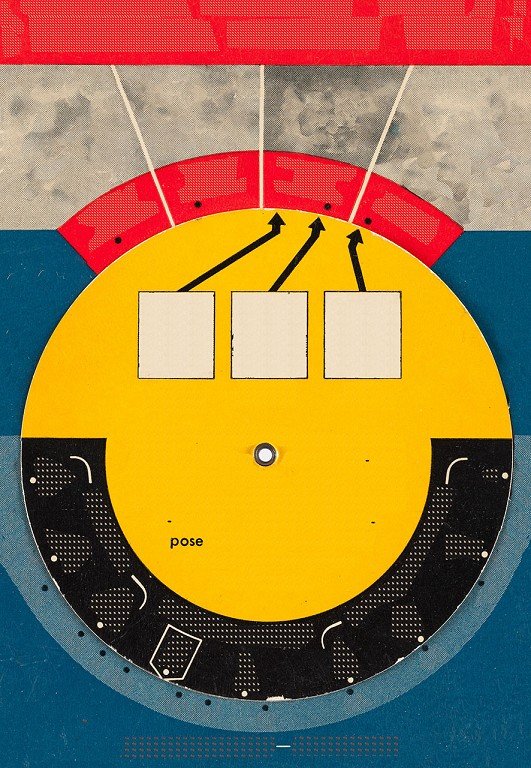

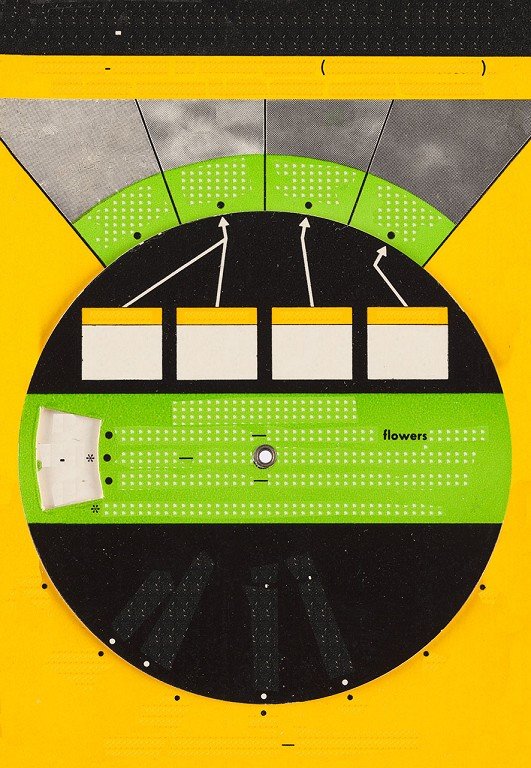

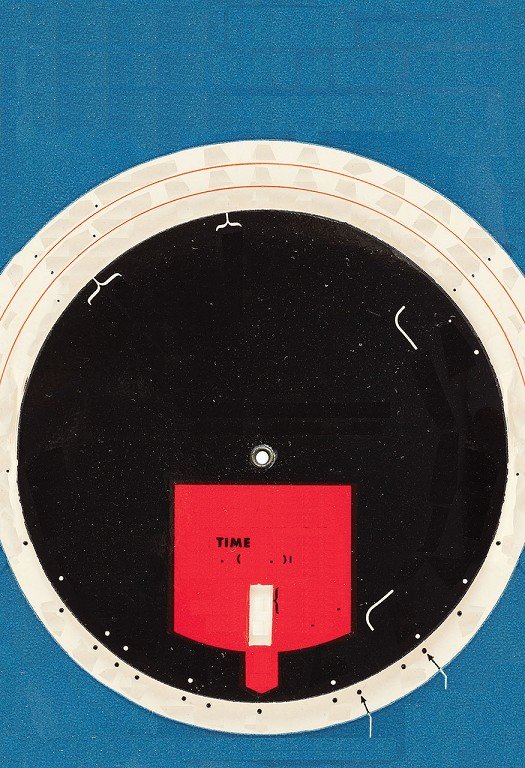

The final two selected portfolios, quite different in tone and approach than those discussed above, speak to the history and nature of photography. Mid-twentieth century charts for establishing exposure and other settings are the starting point for Andy Mattern’s Average Subject/Medium Distance, who digitally strips away their explanatory notations. The once functional, physical objects—analog tools for analog photography—become self-referential digital photographs—objects both beautiful and ironic. Walter Plotnick’s Surprise Inside also combines analog and digital processes and harkens back to an earlier photographic era. His Bauhaus-inspired montages, printed on opened cardboard boxes, echo in their composition and choice of imagery the energy, physical release, and delightful surprise of the act of opening the boxes.

It was a pleasure to peruse all the submissions. There was so much strong and meaningful work that it was difficult to narrow my selections down to ten portfolios. I congratulate all who entered and thank you for your dedication to photography. Now, more than ever, the world needs artists to help us reflect, analyze, and understand our emotions and to give us moments of sheer visual joy.

Barbara Tannenbaum

Chair of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs and Curator of Photography

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Carl Bower

We are not defined by our fears, but I believe they cut to the core of our being in a way that most other feelings do not. I spent several years struggling to extricate myself from a bad relationship and stalking that even extended to other countries. I had to get the police involved and file restraining orders, but these steps were undermined by wavering resolve and my mental and emotional life was a complete disaster. Yet I kept it hidden. I was too embarrassed to share my situation with anyone, afraid of what they would think, afraid of losing work. The longer it continued, the more ashamed of the situation I became, leading to further isolation. It made me wonder what others were hiding, what kept them awake, what they were afraid to tell anyone for fear of repercussions. I knew from experience how well a facade can be maintained, that we cannot trust what we see. Our fears are held closely, and the experience of them is intensely personal and often isolating. I’ve asked complete strangers to share their fears and be photographed. For some, the experience was cathartic. This series examines the dichotomy between our who we are and who we appear to be, of how little we know of those around us and what they carry.

Suzette Bross

For The Glass transforms the flatbed scanner into a contemporary version of the photographic plate. Meditating on the tradition of portraiture, each image mimics the sharp details and imperfections in the surfaces of 19th-century studio portraits. I use digital equipment to return to this slow pace of production by scanning over the subjects as they sit for extended exposures. These portraits capture every movement, which in turn creates unique digital images that cannot be replicated. The relationship between my subjects and myself becomes a performative act of photographing. With the inclusion of my own self portrait in the series, my focus is on the intimacy of the work’s process and my investigations on how one is to interact with the reinvented plate. This series invites the viewer to become immersed in the surface of the image as it magnifies my relationship to the process and an uneasy relationship with technology.

Troy Colby

Hold my hand and hold your breath. I am learning as I pretend to know what I am doing. I am so tired and worry more about you than myself. I am restless in this domesticated life. I long for more for you and myself. Things seemed easy when it was only the pitter- patter of your little feet. Life can be so unkind. I see the way the light hits your face as you cry out for warmth, I see how it hits your face and shows the lines of wisdom, through the good and the bad. We are the quiet and unspoken, yet we scream the loudest. Rest your tired eyes. I will cover you in warmth. We will move past this and carve out our own light against the darkest skies. As the words, Are you Okay fade from our lives.

Sharon Draghi

“Love is the quality of attention we pay to things.”

- J.D. McClatchy

Split Tree Road is an ongoing project about myself, my family and the place we live in. By capturing quiet moments alone, as well as our shared life together, I’m exploring ideas about privacy, intimacy, self awareness and the passage of time. I use candid and staged imagery with the intention of deliberately blurring the boundaries between what is true and what is imagined. I’m also interested in looking at how our environment brings context to our daily lives. The suburbs can be breathtakingly beautiful and sinister at the same time, and I want to show both the peace and isolation that one can feel living out here. Despite the fact that we may be surrounded by friends and family – and if we are lucky we receive love and stability through these relationships – we go through life alone, confronted with our unique fears, struggles, dreams and desires. It is this sense of existential aloneness that I want to capture in my work.

Anna Grevenitis

When my daughter was born, I was told that she had the “physical markers” for Down syndrome. A few days later, the diagnosis of trisomy 21 was confirmed with a simple blood test. Today these “markers” have grown with her and her disability remains visible. As we go about our ordinary lives in our community, I often catch people staring at her, at us. With REGARD, I open a window into our reality. To emphasize control over my message, these everyday scenes are meticulously set, lit up; they are staged and posed.

Glenna Jennings

At Table (2005-2020) documents everyday spaces of expression and connection – dining rooms, kitchens, restaurants and bars in locations scattered around the globe. In the USA, Mexico, Canada, China, Europe and beyond, I use my lens to navigate from a perspective that is local in-depth but global in breadth. I have collected thousands of moments that capture friends, family and erstwhile strangers sharing time around food and drink in spaces where I am also an active participant. Through the messy contingency of plates and bottles and condiments, my “tablescapes” offer subtle moments of drama and humor; gestures, expressions and objects collide to perform as cultural artifacts and personal memories. I see the table as a space that can often transcend cultural barriers to become a place for authentic interaction. For an only child, these photographs have come to represent moments shared with an extended family that defies traditional definition. This makeshift family offers a casual visual anthropology of everyday moments shared by a range of cultures, while also addressing how photographs may function as both imperfect personal memories and problematic shared histories. While I am also interested in moments of material excess (from beer-soaked revelry to abundant plastic tableware) and social rupture (from fatigue and distraction to eye rolls and arguments), At Table ultimately aims to connect, rather than solely critique, aspects of the human condition that collide and converge in a familiar, everyday place – the table.

Dave Jordano

This project might never have materialized if it weren’t for the generosity and support of Fred and Laura Bidwell, art philanthropists and owners of the Transformation Station museum and gallery in Cleveland, Ohio. After becoming familiar with the work I made in Detroit, Fred contacted me and asked if I wouldn’t mind traveling to Cleveland to photograph his beloved city for a week. I felt the invitation was a wonderful introduction to delve into various neighborhoods within the city and discover what inspired me most about this iconic Midwestern city.vCleveland, much like Detroit is a rust belt city made up of mostly blue-collar workers who for decades worked the factories and manufacturing plants that built the American economy leading up to and after WWII.vOver the years, much of these areas have seen de-population, little or no progress in terms of redevelopment and urban renewal and like Detroit, have sustained harsh economic declines. But, there always seems to be a shining beacon of hope and this is what I am always searching for. There is human presence here, and the efforts of those who have remained, whether neighborhood street corner bars, small grocery stores, churches, or even heavy industrial complexes, has always been my intent to honor those who have chosen to remain in place.

I’m a fine art documentary photographer who has spent the last two decades documenting cities in the Midwest, most notably in Detroit and Chicago. I have published four books on the subject.

Andy Mattern

Turning the camera on its own logic, these photographs in Average Subject / Medium Distance reconfigure paper guides once used to determine exposure and other image settings. Stripped of example imagery, technical numbers, and explanatory text, these relics from mid-century photographic practice are reduced to their underlying structure. In the process of removing this information, digital traces are created, shifting the surface into a rupture between physical and virtual, analog and digital, functional and useless. This process creates a new surface that hints at broader formal imperatives in the medium. A single word or two remain in each composition in their original location, while all the other information has been neutralized. These words operate as a springboard for interpretation while pointing to the priorities, conventions, and judgments embedded in the original object.

David Obermeyer

I first met Father Pfleger while working on Spike Lee’s movie “Chiraq,” as the Production Sound Mixer. Prior to filming, cast and crew were invited to attend Sunday service. It was a mixture of song and dance with a powerful sermon by the Father. His words resonated in me, and I attended service every Sunday that summer while filming. I came to realize that Chicago is a better city only when it works for everyone, that until the underserved communities on the South and West sides are given the same opportunities and attention as the Northside, Chicago will remain a tale of two cities. After the film wrapped, I approached Father Pfleger with an idea for a photo project. He brought me to the Strong Futures program, which seeks through mentoring and love to help and find employment for the most underserved young adults in our city.

“Prison or death is what’s here for us” was told to me by one of the mentees, on my first encounter. In Chicago, there are sixty-five to seventy thousand young people between the ages seventeen and twenty-eight who are not in school or at work and deemed “at risk.” In describing them, Father Pfleger, said: “I think they feel like and have been treated like the disposable and the throwaways, I just feel we have abandoned them in this city.”

Strong Futures is not just about employment but will help with all aspects of life; it’s about transformation. Most importantly, it shows that someone cares that they are loved and not alone. Once a week, there is a group meeting, a roundtable discussion of daily struggles, the most common being losing a family member to gun violence, maintaining employment, and navigating the pitfalls of the street. Each meeting starts with the same introduction; name, what brought them to Strong Futures, how their week has been, and the discussion begins. Each meeting ends with the same convocation; we gather round, touch fists, and state. “Our thoughts become our actions, our actions become our habits, our habits become our character and our character becomes our destiny.”

I hope these portraits expose the resilience of a community that, through racism and neglect, has been forgotten and treated as disposable. Strong Futures through mentoring and love seeks to change that narrative.

Walter Plotnick

My photographic collages serve as a metaphor for anticipation, those moments when the unknown is being revealed.

The implied act of opening the boxes, releases the energy of the occupants, allowing them to take flight. The people and objects confined within, through the simple act of unfolding, are exposed, revealing what was previously hidden.

Acrobats, circus performers, and divers come flying out of the opened boxes, all performing daring acts that most people would be hesitant to perform, but we find them exhilarating to observe. I try to convey excitement, and energy in images that are playful, expressive, and nostalgically bring the viewer back to the joyful moments of anticipation felt in childhood.

The sense of nostalgia evoked in the graphic synthesis of these images is augmented through the use of a wash of warm sepia tones that permeate the images. There is also a visual correlation between inhabitants of the boxes and the boxes themselves.

The unusual and dissimilar combination of people and cardboard boxes is visually unified through the repetition of angles. Despite pairing such disparate elements, I bring them together harmoniously to form images with visual impact, and are frankly, fun to look at.